![]()

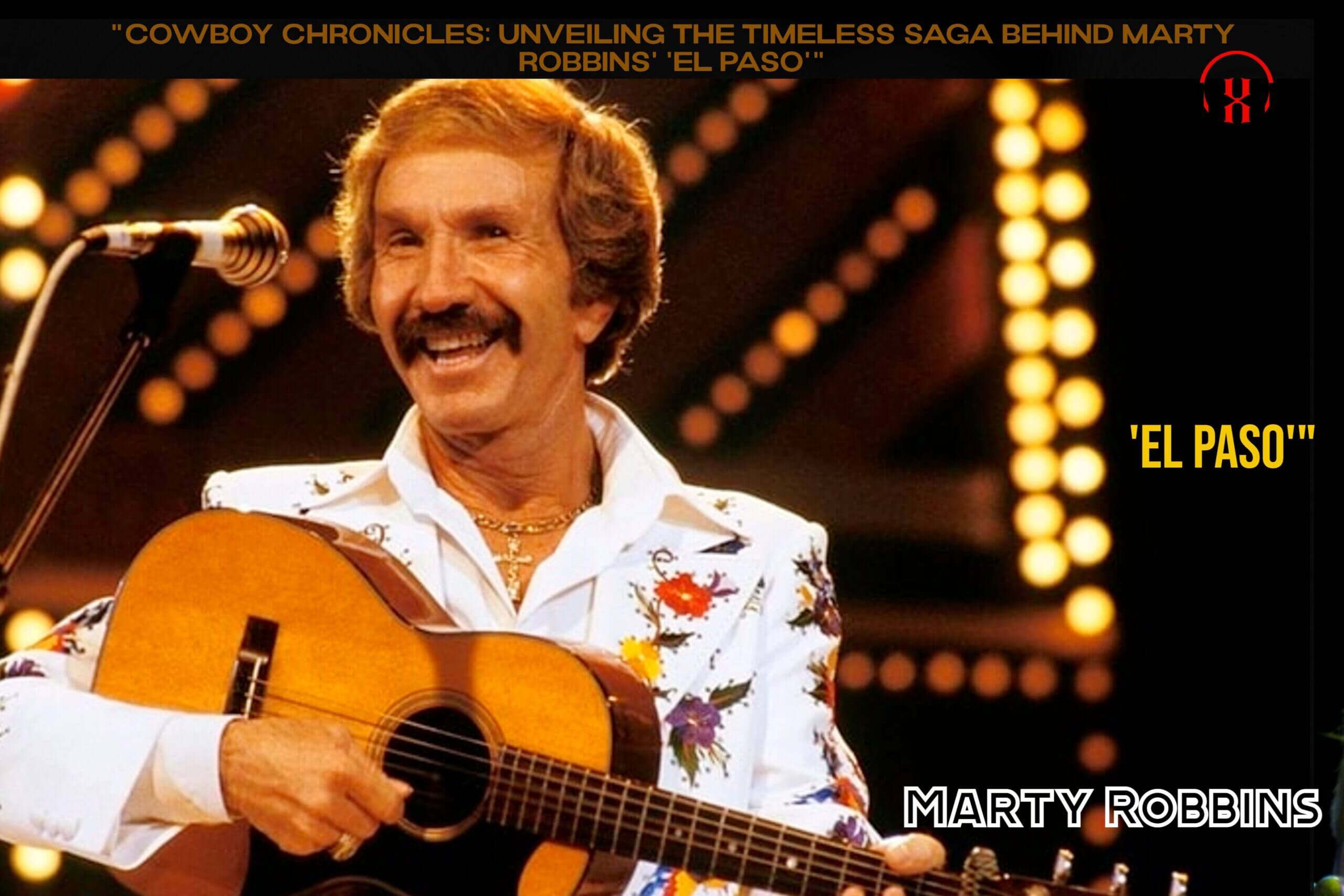

Unveiling the Tale Behind the Iconic Song: Marty Robbins’ “El Paso”

Marty Robbins, a man who often mused that he was born in the wrong era, harbored an undying love for the rugged cowboy life. His heart thrived in the presence of horses, firearms, and the great outdoors. However, Robbins didn’t initially channel this passion into his music career, which began with a focus on more contemporary themes, as evidenced by his 1957 chart-topper “A White Sport Coat (And A Pink Carnation).” It was only when he lent his voice to the theme of the 1959 Gary Cooper film, “The Hanging Tree,” that he ventured into the realm of Western melodies.

It was during this same year that a serendipitous moment changed the course of his songwriting. While driving and listening to the radio, Robbins was struck by Johnny Horton’s runaway hit, “The Battle of New Orleans,” penned by Jimmy Driftwood. This song, based on a historical event, highlighted a profound truth for Marty – the public had a penchant for finely-crafted historical narratives. If a ballad about a nearly forgotten war could capture hearts, then perhaps the same could be achieved with a tale from the Old West, a territory ripe with legendary stories like that of Billy the Kid.

The timing couldn’t have been more perfect. Westerns were dominating television screens, with “Gunsmoke” leading the pack and a myriad of cowboy shows captivating audiences of all ages. The late fifties witnessed a generation enthralled by the likes of Annie Oakley, Roy Rogers, the Lone Ranger, and more. This was the generation that fully embraced the idea of a song about the Wild West.

Having driven through El Paso, Texas numerous times during his tours, Robbins developed a deep affection for the city, its people, and its rich blend of American and Mexican cultures. Consequently, when he set out to compose his answer to “The Battle of New Orleans,” it was only natural to place the Texas border town and its distinct musical ambiance at the heart of his story.

Drawing inspiration from his grandfather, a true cowboy with a life filled with cattle drives and cantina brawls, Robbins began weaving a tale of a cowboy, a captivating Mexican maiden, and a menacing gunslinger. What emerged was a tragic narrative of Shakespearean dimensions, a story he soon discovered wasn’t readily embraced by the music industry.

In the realms of country and pop music, there existed an unwritten rule – songs should not exceed three minutes in length. Record labels believed that longer tracks would fail to engage the audience’s attention. Moreover, intricate lyrics were often dismissed as a hindrance to a song’s success. Robbins’ latest composition, “El Paso,” shattered these conventions. Its runtime stretched to a daring four minutes and thirty-eight seconds, a feat considered impractical for radio airplay. To complicate matters further, the song didn’t fit the prevailing trends of rockabilly and shuffle-beat honky-tonk music. Lastly, its storyline, ending in tragedy, didn’t align with the upbeat and cheerful tunes of the time.

Marty Robbins, however, was undeterred. He believed that his live audiences resonated with the song’s tragic yet compelling narrative, a testament to the enduring power of love. Robbins implored country radio programmers to give “El Paso” a chance, confident that it would attract new listeners to their stations.

Released in the fall of 1959, “El Paso” arrived at radio stations just as “The Battle of New Orleans” relinquished its hold on the top positions of both the pop and country charts. It seemed serendipitous, almost as if the market was ready for another historical ballad. Soon after Christmas, the song that many had doubted would find a place on the radio climbed to the summit of Billboard’s country singles chart, reigning for seven weeks. Remarkably, it ascended to the number one spot on the Hot 100 pop chart, establishing itself as one of the few records to conquer both the country and pop charts in the 1960s.

Recorded during a marathon eight-hour session in Nashville’s “Quonset Hut,” “El Paso” was accompanied by simple yet evocative Spanish-flavored guitar work by Grady Martin and harmonious backup vocals by Tompall and the Glaser Brothers. The song defied convention, capturing the essence of the Wild West in a way that felt entirely novel.

In 1976, Marty Robbins revisited his most famous hit with “El Paso City,” offering a twist to the original narrative. The song suggested that the narrator could be a reincarnated version of the cowboy who met his end in the original ballad. Collaborating once more with Grady Martin, Robbins soared to number one on the charts, marking his triumphant return to the top.

“El Paso” has transcended the status of a mere song; it has become a piece of history. Much like Bob Nolan’s “Tumbling Tumbleweeds,” Marty Robbins’ ballad embodies the spirit of the American West. The fact that the song’s events were fictional matters little, just as the fact that tumbleweeds arrived in the West decades after they were immortalized in song. “El Paso” taps into the romanticized vision of the frontier, forging an unbreakable bond between cowboys and country music that endures to this day.

Artist: Marty Robbins

Nominations: Grammy Award for Best Country & Western Recording

Genre: Country

Lyrics

Out in the West Texas town of El Paso

I fell in love with a Mexican girl.

Night-time would find me in Rosa’s cantina;

Music would play and Felina would whirl.

Blacker than night were the eyes of Felina,

Wicked and evil while casting a spell.

My love was deep for this Mexican maiden;

I was in love but in vain, I could tell.

One night a wild young cowboy came in,

Wild as the West Texas wind.

Dashing and daring,

A drink he was sharing

With wicked Felina,

The girl that I loved.

So in anger I

Challenged his right for the love of this maiden.

Down went his hand for the gun that he wore.

My challenge was answered in less than a heart-beat;

The handsome young stranger lay dead on the floor.

Just for a moment I stood there in silence,

Shocked by the FOUL EVIL deed I had done.

Many thoughts raced through my mind as I stood there;

I had but one chance and that was to run.

Out through the back door of Rosa’s I ran,

Out where the horses were tied.

I caught a good one.

It looked like it could run.

Up on its back

And away I did ride,

Just as fast as I

Could from the West Texas town of El Paso

Out to the bad-lands of New Mexico.

Back in El Paso my life would be worthless.

Everything’s gone in life; nothing is left.

It’s been so long since I’ve seen the young maiden

My love is stronger than my fear of death.

I saddled up and away I did go,

Riding alone in the dark.

Maybe tomorrow

A bullet may find me.

Tonight nothing’s worse than this

Pain in my heart.

And at last here I

Am on the hill overlooking El Paso;

I can see Rosa’s cantina below.

My love is strong and it pushes me onward.

Down off the hill to Felina I go.

Off to my right I see five mounted cowboys;

Off to my left ride a dozen or more.

Shouting and shooting I can’t let them catch me.

I have to make it to Rosa’s back door.

Something is dreadfully wrong for I feel

A deep burning pain in my side.

Though I am trying

To stay in the saddle,

I’m getting weary,

Unable to ride.

But my love for

Felina is strong and I rise where I’ve fallen,

Though I am weary I can’t stop to rest.

I see the white puff of smoke from the rifle.

I feel the bullet go deep in my chest.

From out of nowhere Felina has found me,

Kissing my cheek as she kneels by my side.

Cradled by two loving arms that I’ll die for,

One little kiss and Felina, good-bye.

Comment on ““Cowboy Chronicles: Unveiling the Timeless Saga Behind Marty Robbins’ ‘El Paso'””